The politics of the moment were heated more than either of us had ever really recalled.

That rainy October in Paris before the election. We sat on the steps of Sacre Cour and looked up the forecast. Hillary Clinton’s grinning face sat at the end of a long blue line that said 90%. You screenshot the graphic and sent it to Robert who wrote back, “I’ll see you in January.”

You called me in January, around the time of the inauguration, close to tears because there was no visa left that would bring you back to the states. You explained everything in detail, and because of your lack of English, I couldn’t really follow logistically why you couldn’t get a visa. It didn’t matter why. “Why don’t we just get married, then?” I said.

I remember eating shrimp and grits in this old family tavern in Columbia, South Carolina called Yesterdays telling my aunt over the phone that I was getting married. And she assumed a noble tone and congratulated me and then I went on to break down in tears (I couldn’t even tell if they were real or fake), and say that we wouldn’t be getting married if the person she voted for hadn’t won. That you would have been able to come here and work and we wouldn’t be forced into an early wedding. She maintained a diplomatic motherly tone and assured me she was happy for us and said she couldn’t wait to meet you.

You are seven years younger than me but much more responsible. The other day we were looking for AirBNB’s for our delayed honeymoon in Hawaii (where my parents spent theirs), and you had to pay for the reservation because I didn’t have the money. You checked your account on your phone and had over five thousand dollars in your savings. Five thousand more than I knew you had. “When did you get that money?” I asked. “I’ve been saving 20% since the holiday,” you replied. I raised my eyebrows, a faint gesture to hide my juvenile shame about money. “You can do that too, you know?” you said in a tone that was neither belittling nor sarcastic.

You lived in the 2nd district. We usually had to walk through this street that was lined with gay video stores. Signs for poppers everywhere would occasionally send me into a triggering spiral until one day I noticed that one of the signs said, “POOPERS HERE.” I laughed out loud with relief, as if the humorous misspelling had saved me.

We bought these two $80 copper rings three weeks before our wedding at this design shop in Provincetown. You visited me for a weekend while I was there because I had composed a version of Romeo and Juliet and it had been randomly selected to be produced at a theater in Wellfleet. You took care of most of the wedding planning while I spent my days exploring the wintry cape, and my nights portroying Juliet’s mom and playing the piano to a barely half full house.

I lost my ring five months after we were married. I was rehearsing with a drummer at the rehearsal studio on St. Marks Ave. and I put the ring on one of the knobs of the keyboard because it was getting in my way while I was playing. When I called the studio three hours later, they couldn’t find it and guessed it had been taken by the people who rehearsed after me.

Marriage, to me, seemed like a right everybody should have but that nobody should ever take seriously. All the things that went with being married: the wedding, the ring, the appearing a certain way, I could have done without; but my politics bore within me a desire to utilize the right we had recently won. A newfound fear that it could be taken away lurked in the background. Everything about our situation pointed to one option: do it and don’t look back. The rest will figure itself out. When close friends, sensing my ambivalance about the whole thing asked, “So do you want to get married?” I would say that obviously we are getting married so early because of the situation, but I could have seen us getting married in the future anyway. But inside I was thinking, “this has nothing to do with what I want.”

I was in a rehearsal at BAM with a new project about Rimbaud when the Supreme Court ruled same-sex marriage was legalized throughout all the country. I was looking at my phone and saw the news, and interrupted the director mid-sentence. “Gay marriage was just passed,” I said in disbelief. I was twenty-six. Ripe marrying age, and the youngest person in the room. There were two other twenty-something gay guys in the cast and they both were overcome with a sense of shock. The director, who was also gay, acted as if the news were a bit disruptive to his process.

I posted this status on Facebook: “I am unbelievably and immediately transformed by this news. This is one of the best days of my life. So grateful to see our nation making progress in the right direction and that our LGBT community will not have to wonder if they are considered equal humans any longer. Oh my God, I feel like I just woke up from a lifelong bad dream! This is huge!”

There was no way of knowing that you, my future husband, were just a year away from moving to New York City for an internship. That I would see your pop up on Grindr and go to your new basement apartment in Crown Heights to meet you.

We borrowed my dad’s SUV in Detroit our first Christmas as a married couple, and drove down to New Orleans and back, stopping through Nashville and other places along the way. It was a used car, as my dad sells used car, so it had no input or bluetooth to play music so we were forced to listen to the radio, which I kind of enjoyed because I got to listen to crazy conservative talk radio. The further south we got, the more Christian Rock stations there were. You claimed that Americans were crazy about politics and that French people didn’t care that much; and I thought two things: 1. That maybe your particular people in France hadn’t been that political because they were more concerned with things like fashion, parties, and instagram. 2. That America hadn’t ever been this flaggrantly insane to me until quite recently.

99% of the time, you do our laundry. You’ve turned our house into a home interior designers would salivate over. Your presence in my life, often times seems magical. Like all my weaknesses or flaws are somehow manageable because you so capable. This feeling is accompanied by a sense of guilt. That I’m still unable to take care of myself. That you could find somebody capable and put together like yourself.

At the end of February of this year, I had been sober for three years. I was packing my suitcase, (the hunter green floral patterned one my mother handed down to us) to go to Abu Dhabi and Shanghai for a project with New York University. I opened the small pocket and you jumped up from the bed yelling “Stop!” Inside was a brown envelope that was supposed to surprise me on my trip. In the letter, you congratulated me on my sobriety and told me how proud you were of me.

Your family didn’t come to our wedding. Your father, who wasn’t talk to you at the time, wouldn’t allow your mother to fly out from Lyon. I met your little sister Karen the following summer. As you two were making pancakes one Sunday morning, she began to cry, you said, because she realized how real the wedding had been. It was just dawning her that she hadn’t been able to be there. Between you and Karen, I often wondered how two kids from the same family could have such impossibly sensitive hearts.

As I write this, almost a year after our wedding, I still haven’t met your mother or father.

I was chain smoking cigarettes with my opiate addicted roommate, Rob, as we realized Florida was going red. “There has to be a way this is going to be okay,” Rob kept saying. You were six hours ahead me, and my Facetime call woke you up. “Babe…it didn’t go our way,” I said. And you realized that you weren’t going to be getting your for-certain-dream-job after all.

On our road trip, we stopped at Oak Alley Plantation in Lousiana, William Faulkner’s house in Oxford, Mississippi, and then the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. Before this trip, contextualizing race relations in America seemed impossible. If standing in a slave hut and then the exact spot they shot MLK wouldn’t make it clear, then nothing ever could. You walked through each museum with an inconspicuous reverence nobody I’d dated before could ever muster.

You find American liberal inclusionism a little obvious, on-the-nose, and therefore annoying. Last week we saw Love, Simon (another olive branch from me to homonormativity) and the fact that he ended up with a black Jewish boy annoyed you, not because he was black and jewish but because you could feel the writers congratulating themselves for having him end up with a black Jewish boy. I argued that perhaps they should congratulate themselves and that maybe it will seem novel and agenda driven until it becomes normal.

Last week, the White House released its annual photo of interns. All white.

To be married to a French person is to have opted in and out of the mainstream. To Americans, the French are both more exotic but also more pretentious.

I would be lying if I said the feasible possibility of one day moving to Paris, while America quickly deteriorates wasn’t a factor in getting married.

Before you even knew you were gay, I was stumbling drunk on red wine through the midnight streets of La Marais. I was eighteen. It was my first time in Europe. I had met a British professor at a café who insisted on letting me tag along with his group of friends to the different gay bars in the area. Around four in the morning, with a drunken and serious conviction, he stared in my eyes and said, “I’ve been watching you all night, and you are different from most boys, I have to say, you are going to lead a curious life, and you can’t let anybody take that away from you.” And that wasn’t even close to the first or last time a stranger has told me something like that.

Sometimes I am afraid that being married is the opposite of that curious life.

It’s undeniable that the structure our relationship provides has allowed other aspects of my self/creativity/career to flourish. My life has improved since you came around, even though I’ve always been clear that my happiness isn’t dependent on our relationship; an obvious way to keep a wimpy upper hand.

People joke that I found a French version of myself. We are the same height. We both have dark hair, but yours has a golden tint in the sun which I’m very jealous of. You have the hair and face of a French cologne model. I have more the face of a cute beatnik artist who has beautiful eyes but a troubled youth hidden in his jaw.

My senior year of high school, in order to re-enter a Catholic School I had left because I was afraid of coming out of the closet there, I had to take an English course at a community college to regain credits not available in what was deemed the inferior public schooling system. I took a writing course online, only having to meet with the professor once. For my final paper, we had to write a persuasive political essay. I felt completely radical writing about gay marriage. I fantasized about the professor giving me a C even though the paper was good, simply because he was a bigot. He gave me an A and nobody else ever read it.

Writing was always a way to justify or make sense out of where I was, and the compulsion to write usually happened when enough questions had built up that was I forced to examine. Sometimes I’m afraid nobody might ever know the beautiful hidden syapses of meaning that have made up my short life. I wish I could say that my writing could one day help somebody else, but I’ve written enough now that has never been read so I can’t know for certain whether or not that sentiment is even true. I think I write because I want to believe somewhere that I am “good thing”.

When I was in high school, my sister Maria got her hands on a puppy because she was going through a rough time. It was this little black runt of a dog she named Bueller after Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. Her friend adopted Bueller’s sister who looked exactly the same and named her Dory. Bueller and Dory would run the beaches of Lake Michigan in South Haven while their owners made bon fires and drank beer. Maria was 19, dropped out of Western Michigan University, but still living in the student ghetto of Kalamazoo. That summer the dog became her avatar. Waiting for her outside the bathroom as she showered. I had never seen a dog so loyal and sweet. Sleeping at the foot of her bed. Bueller knew it was Maria’s.

The winter before we met, I came home to my apartment and there was a guy sleeping in our lobby. I said hello like it were normal that he were there; and honestly, living in Crown Heights in 2016, it didn’t seem that strange that a person might be sleeping in your lobby. He didn’t say hello back. Just stared at me with a glazed off stare that helped me realize he wasn’t even by homeless standards, stable. He was there for about a week when a pink notice on the front door of our building, “Please call management if you find people sleeping in the lobby. If management is unavailable, please call 911.”

I once vowed to never be one of those writers that would romanticize the cramped filthiness of certain New York City apartments. But the romance of New York is stronger than my resistance. The summer I met you was the summer the occasional two or three waterbugs in our kitchen multiplied into over two hundred. Open a silverware door, three or four or ten would go scattering. We never used the kitchen until I paid $400 to finally have them exterminated.

When you visited New York the final week of November, after the election, we stayed at my friend Amanda’s place in Jackson Heights, because she was out of town and needed me to feed her bunnies, Auggie and Soap. The whole place smelled like a petting zoo.

One night you lit some candles and drew a bath. Thirty minutes later, Amanda’s downstairs neighbors were banging on the ceiling. We had forgot the water was running and the bathroom was completely flooded.

You came bearing a gift. You printed and bound the google doc that was my manuscript for a first draft of the first book I’d ever written: a memoir about being young, gay, and twenty-something in New York; which was really a slow reckoning with addiction. You even designed a cover. Inside was litany of romances and you admitted that designing the cover was a way for you to claim a higher place than any of those men featured in those stories from the past.

I think it was the first time you saw me cry. I had never held my own book in my hands before.

The last time you saw me cry, we had just found out that the wait period for your adjustment of status with Immigration had arbitrarily increased from 17 months to 33. Another year stuck in this country, without seeing your family. Through tears I said that I was afraid that if you knew it was going to take this long, you wouldn’t have married me. And you held me and told me that wasn’t true.

Remember, we were sitting in Time Square Diner and talking about getting maybe getting married? We even looked up the process online. We both seemed super excited about it at the diner but then on the train back to Queens, you could tell I was nervous. You said we didn’t have to think about that now and that you didn’t want to scare me into marrying you, which I thought was a very funny way to put it.

Maria would come to our parents once in awhile with her boyfriend at the time. Bueller was never more than six feet away from her. Never barked. Always friendly but ferociously attached.

That summer, my parents, my brother and I were caravanning with family friends to go camping in Northern Michigan. As the car I was in (I can’t remember) was pulling up to a gas station, my Mom got out her car and ran toward us. Her face was red and panicked. “Bueller was hit by a car!” she cried. And I got in the car with my Mom to drive three hours to Kalamazoo while the others drove north.

Mom smoked probably two packs of cigarettes on the way.

Maria sat on the wooden porch of her student ghetto house with an orange recycling bin on her lap. My mom parked the car and ran to give her a hug and Maria stayed seated, staring at her dead dog. Her roommate had let him off his leash, and when Maria came home and parked her car across the street, Bueller, in loyal form came running to her and was hit by a car in front of her eyes. Now he was mangled, bloodied, wrapped in a towel.

It was a hot and quiet day. Over ninetie degrees.

When Jason arrived, he seemed grave and emotionless, the way men always did to me when bad things happened. We got in my mom’s car, and put the recycling bin with Bueller in the trunk. My mom would ask Maria in a sweet tender tone we only heard when truly tragic things happened, if she needed food or water or anything at all, and Maria couldn’t reply. And we stopped at a hardware store and bought two shovels and then we drove to Lake Michigan.

I can’t remember why but we all decided to leave our shoes in the car, which was stupid because the sand was extremely hot. I carried the shovels and Jason took the bin, but Maria grabbed it and said she needed to carry it. We walked over the dunes to the shore of the lake. Endless and still. “We were just here last week,” Maria said again and again. “We were just here last week.”

Some weeks after the guy showed up in our lobby, my roommate Rob called the building management on him, which annoyed me because Rob was illegally subletting and wasn’t on the lease so now the building management knew and were pressuring me to kick him out. But they still called Rob to ask if that guy had been hanging around. It became an obsession for Rob and he talked about the guy all the time. “The lady downstairs told me he used to live in our apartment until his Mom died,” he said. “And now they’re saying he doesn’t have anywhere to go.”

The next time I saw him in the lobby, the glazed look in his eyes was no longer simply and mysteriously unstable; I now interpretted it as the look of somone staring down the person who stole their home.

The sand was so hot that as we climbed back up the dune to the woods where Maria wanted to bury Bueller, the bottoms of our feet started to burn. My first impulse was to try and protect my mother, who had never been one for the outdoors, but she simply barreled up the hill and didn’t complain. The ground had burnt orange pine needles, another obstacle for our bare feet, but we marched forward. Jason began digging a hole, and I helped. Mom sat in a place where she could watch both us and see the lake.

When Maria laid Bueller in the hole, and grabbed the shovel from Jason to cover the body in soil, she let out a cry so primal and raw my entire body froze and trembled. My mother made a face I had never seen and Jason dropped his shovel and sat on the ground putting his head in his hands. We all knew that that damn perfect dog was a period at the end of a confused and convoluted sentence.

On the way back down the dunes, we noticed a black speck dashing across the sand. Down the ways, a group of college kids playing frisbee. “That’s Dory,” Maria said. And not ten minutes after we buried Bueller did his twin sister come running up to us on the beach, kissing Maria’s face and jumping with glee.

Your mom texts you very sweet salutations. Terms of endearment that in their foreign obscurity seem both sacharine and secretive. We never say I love you in French and if we do it seems kind of like a cute put on. But I have Rosetta Stone and have been practicing. Maybe that will change.

I’d really like to write not from some elevated vantage point where I know more than I actually do; but just tell the story. But the pressure to have insight for a reader, or to discover it for myself, does seem to be the point of most writing these days. If there is an agenda, there is always somebody more qualified than myself.

We were discussing the term ‘performance artist’ and why it made us cringe. “Artist is one of those titles that should be granted by others, not by yourself,” David Cale once quipped over a cup of coffee at Café Reggio. “Like saint.”

When I called Maria and told her I was getting married she gave me a more excited response than anybody. I’m not sure if it was the midwest girl just generally being excited about weddings thing, or if it was because it was her brother….or because of it being a gay wedding. She began to send pictures of cute backyard wedding designs on pintrest. A week after I told her, she called and told me that she & Mychal were going to send us one thousand dollars to help pay for the wedding.

You spent a lot of time worrying about the weather. It was the end of April and you were afraid it was going to rain and that your ideas for your design would be ruined. I would always approach the topic with a “what-will-be-will-be” kind of attitude and this seemed to agitate more than comfort you. In one of my naively idiotic moments, I told you I didn’t really care about the wedding, I just cared about being married to you. This did not go over well.

The three days that was our wedding weekend remain the strangest dream days of my life. Your Uncle Allain came to be your best man. My family drove ten hours from Michigan. I met them at the AirBNB I found them on Dean Street. A purple brick fire-house type apartment. I’m not sure they’d ever been in quarters so cramped.

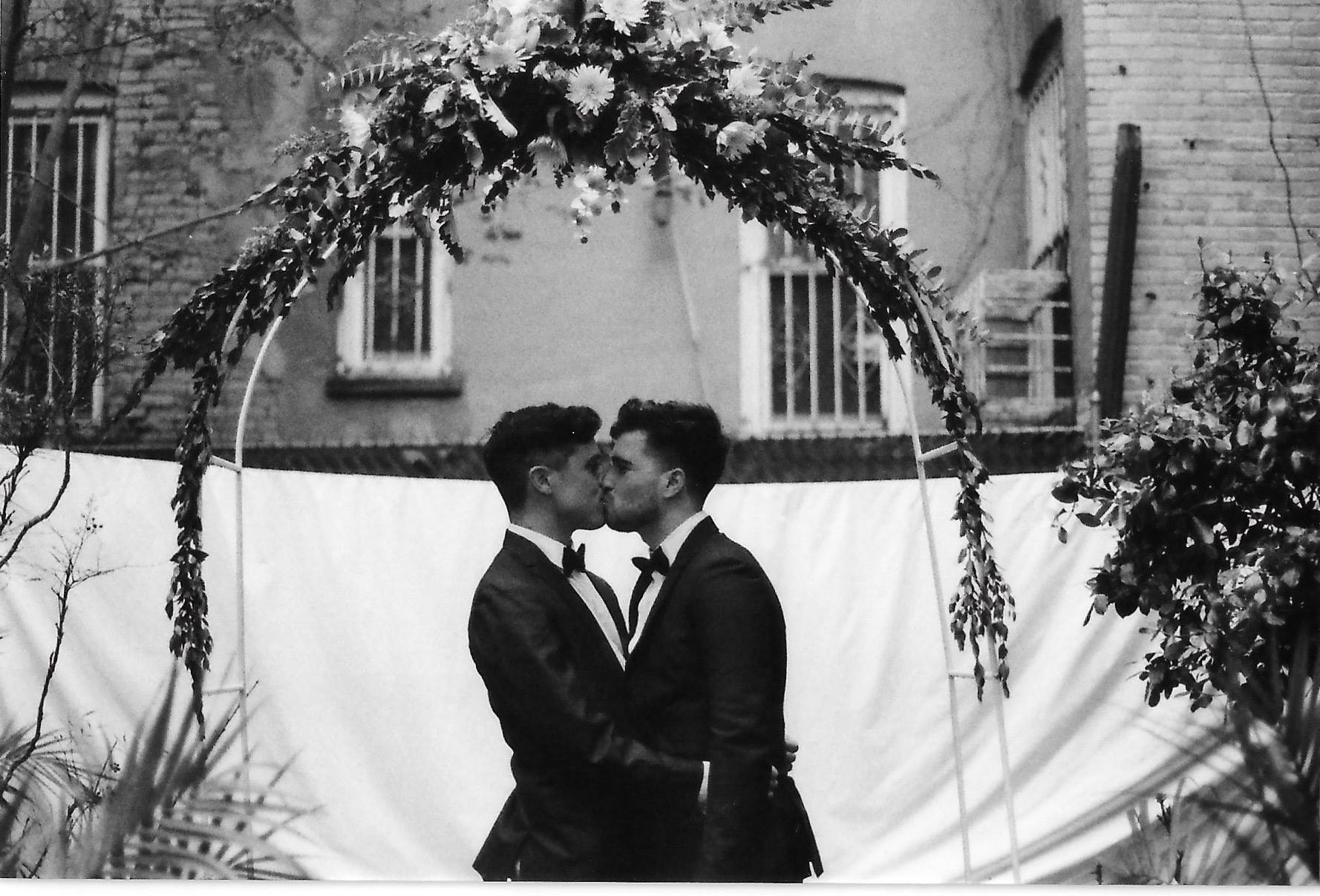

We woke up to rain. My Dad and Sarah’s boyfriend spent the day running to the hardware store, buying two-by-fours and a white tarp and constructing a tent in the backyard. Your friend, Emriech took a bunch of weed-looking flowers and turned them into the most beautiful flower arrangements I’d ever seen. Kate had people running errands. Hunter and Greg came in the final hour and started hanging disco balls and string lights. It’s hard to say, but I’m guessing about forty people helped build the wedding. My favorite part was watching my family and your French friends team up; communicating with hand gestures, giggles, and facial expressions.

When we entered for our first dance, I fell down the stairs. In front of everybody. Like everybody was waiting at the bottom and I fell on my ass and slid down the entire staircase. And then you picked me up and all our friends made a circle around us and sang God Only Knows while my brother played guitar. And you cried and said, “I’m sad.” And I said, “I know.” And we both knew it was because your family, particularly your mother, wasn’t there.

There were a handful of people who voted for Trump at our wedding. They seemed to have just as much fun as everybody els